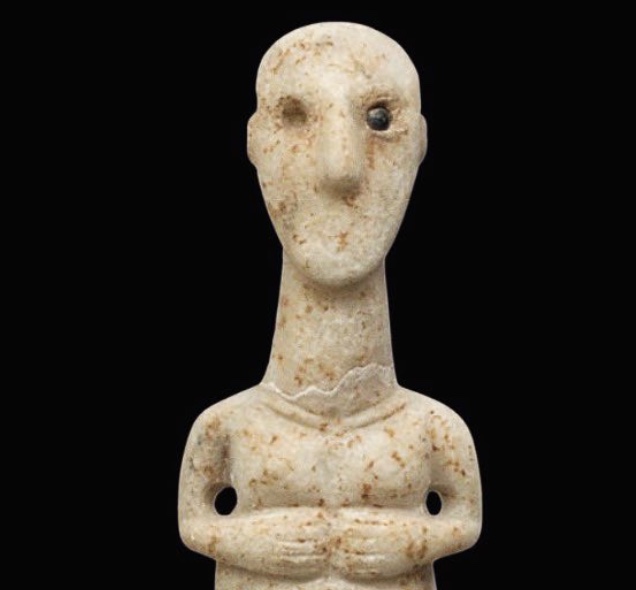

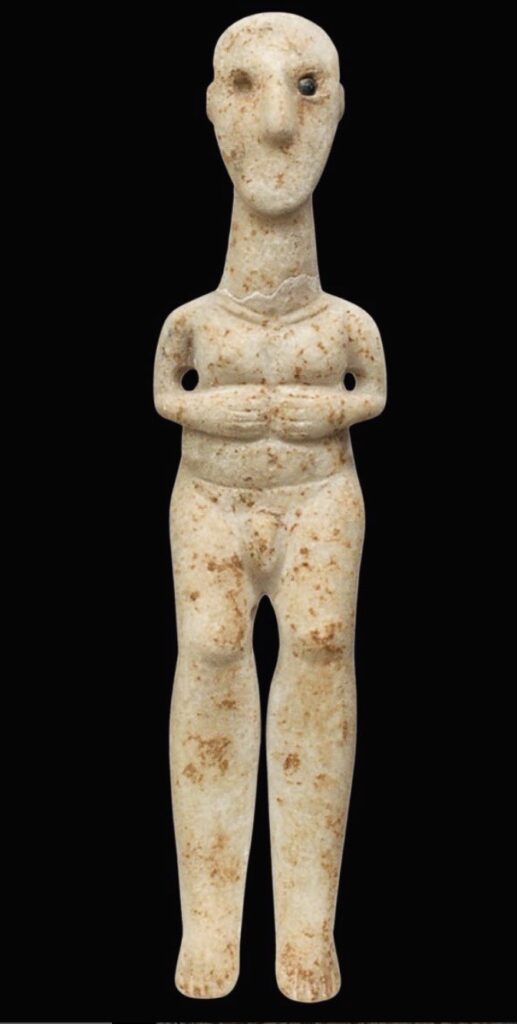

This little marble fellow in Athens is pretty special. He hails from Amorgos in the Cyclades, where during the third millennium B.C. figurines developed slightly differently to their brethren on other islands. He belongs to the so-called ‘Plastiras’ type – an early (and potentially short-lived) experimentation into rendering the human form, and one that veered less minimal, more three-dimensional, and more technically ambitious than the frequently encountered ‘Spedos’ variety.

Coming at the tail end of the Neolithic period, the technical considerations of these sculptures are mind-blowing. Without the use of metal tools, the artist would have painstakingly shaved and bored the figure into fruition with obsidian and emery (both plentiful in the Cyclades, like its famous white marble). Difficult even for a simple figure and downright dastardly for this one in particular – extreme among his kind.

The arms are folded over the abdomen in a canonical style (fingers incised), but with cutouts drilled out at the elbows to liberate them from the body; the neck is long and tapering; eyes, clavicle and navel are all rendered with bore-holes. All tough, since with each of those interventions there would have been considerable risk of fracturing the marble – the neck has fractured and been reconnected in modern times.

But it is those extraordinary legs that really get me. Separately carved legs were a special feature of Plastiras figures abandoned later on – for obvious reasons they were especially prone to breaking, and quite often seem to have done so during carving or soon thereafter, and many show painstaking repairs (aligned boreholes to be joined together). Here, the legs are carved separately tiptoe to groin, with scant millimetres separating the calves.

Unfathomable. The single surviving eye inlay of polished dark stone (exceptional like everything about him) still utterly inscrutable nearly five thousand years later.