What happens when you transform the face of a pudgy young potentate into that of a dour old military leader? A peculiar portrait, indeed!

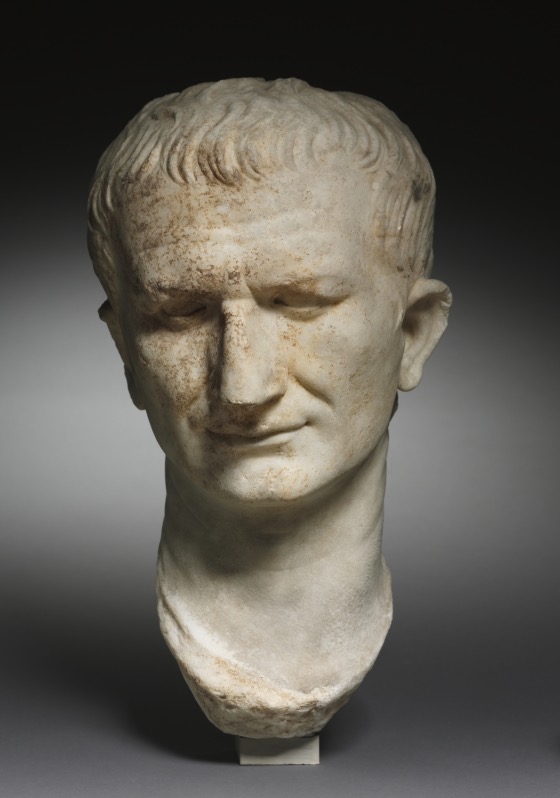

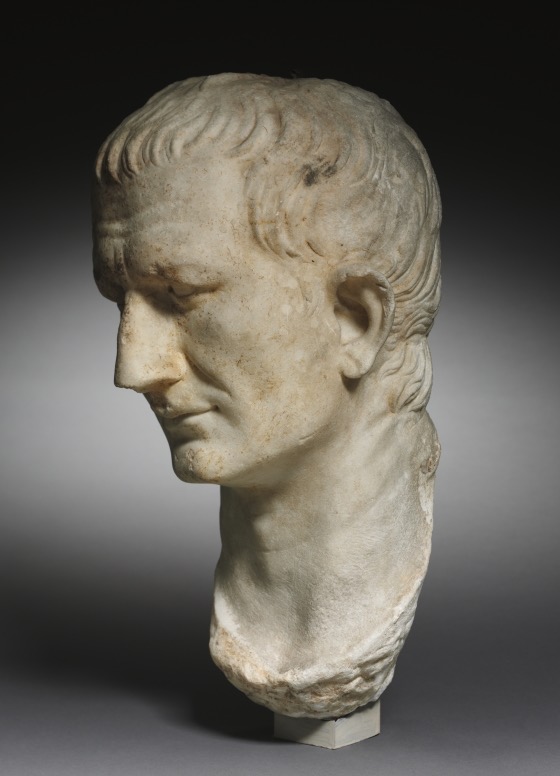

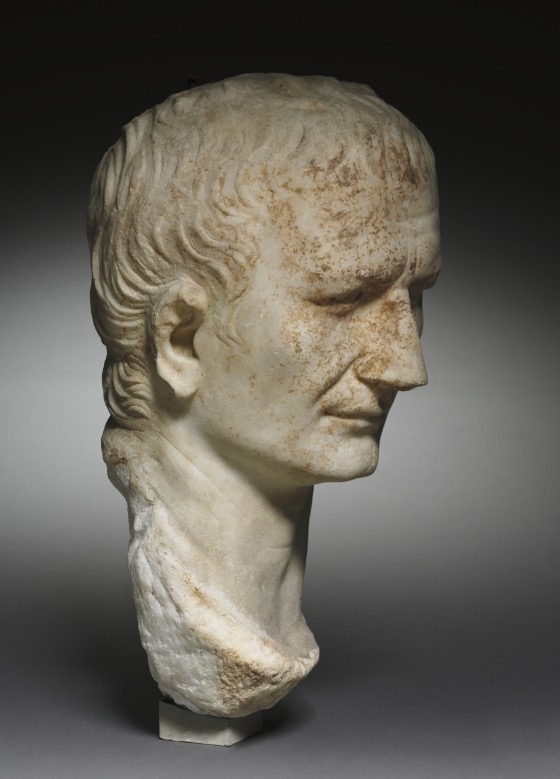

The head is now in the Cleveland Museum of Art, acquired in the 1920’s when it was attached erroneously to a toga-draped body. The peculiarities alluded to are the weird tilt to the head, sardonic puss, jug-ears, dominant brow, a near mullet, and a treatment of the sculptural surface that flattens the planes of the face at the same time as graphically rendering wrinkles. And they are down to a most turbulent time in the early Roman Empire, and the distinctly Roman tradition of damnatio memoriae – taking the images of ‘bad’ emperors’ ‘out of commission’ (so to speak) by defacing them or reworking them.

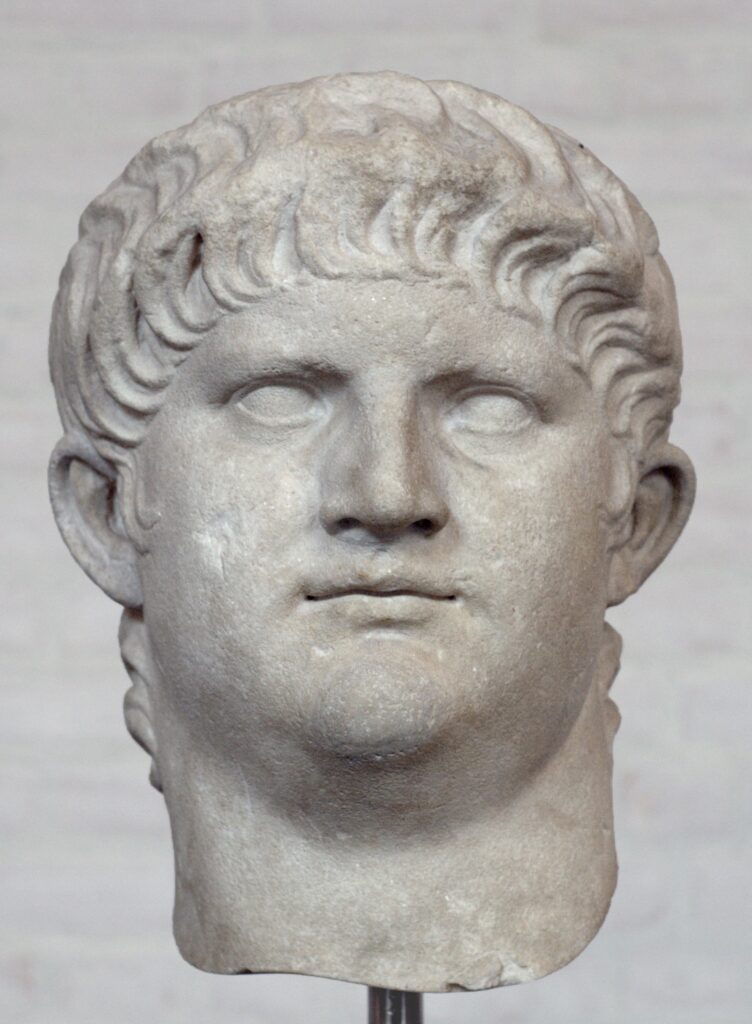

The young emperor Nero had been deposed and assassinated in 69 A.D. (famously fiddling while Rome burned). He was widely panned as a flamboyant nut by historians from his century until our own. In his last portrait type, he became quite chubby, with a pronounced double-chin (he was prosperous!), eyes disappearing into his flesh, and a distinctive recessive lower lip (shown below in Munich). Not a good look, but maybe pretty great if you’ve been tasked with his re-carving.

And what a rehabilitation! Nero’s eventual successor was his polar opposite, and by design: Vespasian was a canny military man, radiating stability and common sense. His best known portrait is an ostentatiously wrinkled countenance in Copenhagen, with hooded eyes and benign partial smile. This one applies those traits superficially – and Nero’s burgeoning flesh must have been a help to the sculptor. Here the gorgeous smooth Julio-Claudian visage has been reduced, the facial features recarved with wrinkles and folds worked in. The hair has been thinned, but still grows (alarmingly) bushy down the neck. The flesh of the face carved lower means that the surround (ears, fringe, etc) stand out all the more. A wild and weird transformation (discovered by John Pollini and published thusly in 1984).