Used to render the divine flesh of cult statues in ancient Greece and Rome, there is a sort of otherworldly warmth to ivory that lands differently to carved stone. The survival of ivory sculpture is rare, and of life-sized statuary practically unheard of.

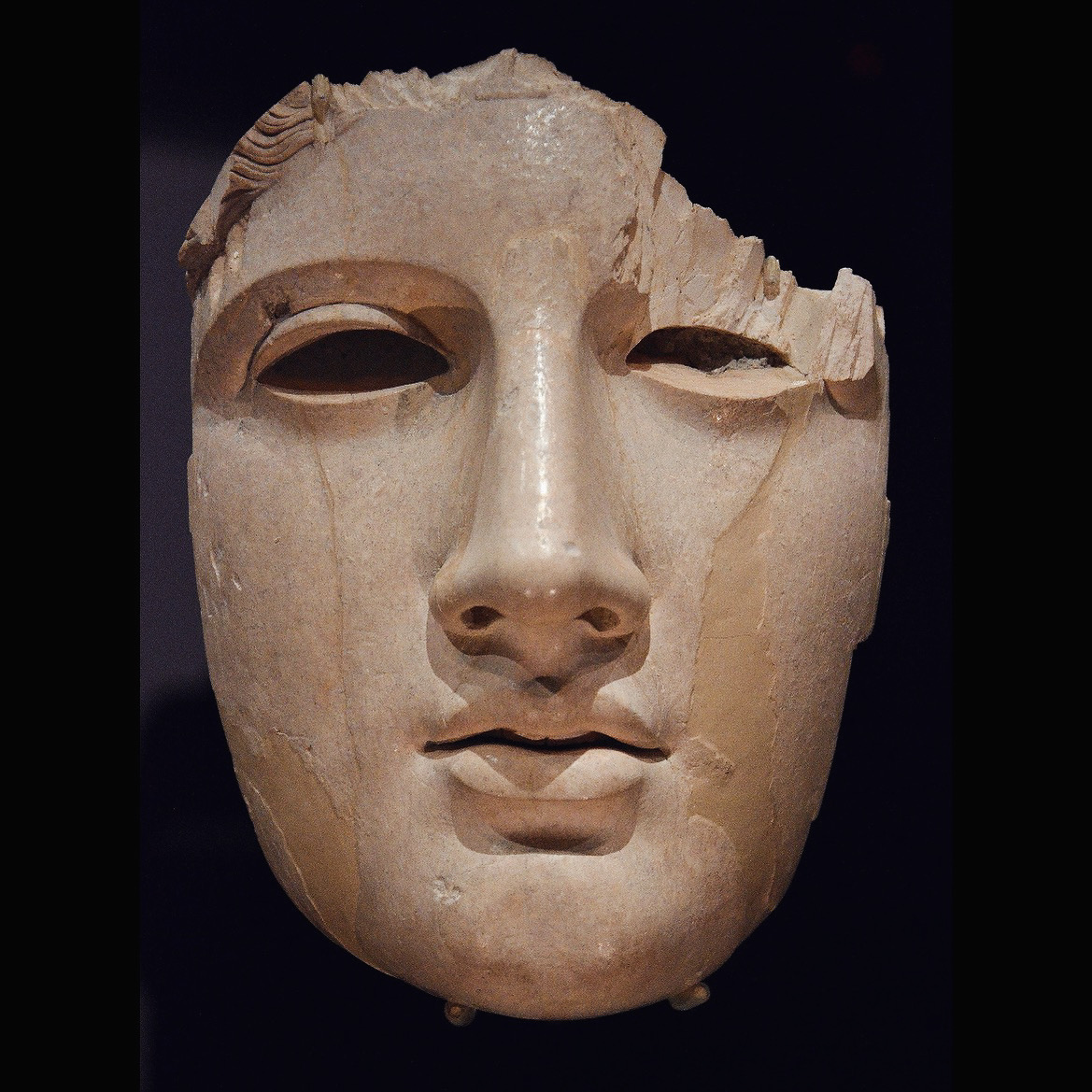

This most miraculous survival now at the Palazzo Massimo in Rome preserves the face of Apollo. And what a face! Sharply delineated eyebrows, strong noble nose and best of all a mouth that seems to breath with lips slightly parted to reveal the nearest hint of teeth.

Since it’s discovery (more on that below) attempts have been made to link it with a lost masterpiece of Pheidias, the legendary 5th century B.C. mastermind behind the chryselephantine cult statues of Athena Parthenos and Olympian Zeus. These colossal cult statues were built upon wooden armatures, with elephant ivory unfurled (if you will) and used for into the areas of the deities’ exposed flesh, whereas the sumptuous clothing was fashioned from gold. While romantic to imagine this is a work of the great Athenian master, it is far more likely a Roman creation.

Found by tombaroli (looters) north of Rome in 1994, the ivory face entered the less savoury levels of the international art market via Switzerland until resurfacing ten years later as part of Italian investigations into the activities of the notorious Giacamo Medici. By the accounts of the looters (well after the fact), it was found in a cistern with a hodgepodge of material (related and unrelated); gold attachments were (allegedly) tragically stripped off and liquidated separately.

Archaeological context is a tricky thing. In Apollo’s case, buried in a secondary deposit , perhaps not all of his story and original display context could have been reconstructed if excavated scientifically. But some of it could, and that it wasn’t is heartbreaking. But be heartened: in his final home at the Palazzo Massimo, Apollo is luminous, presiding with otherworldly grace in the dramatically lit room.