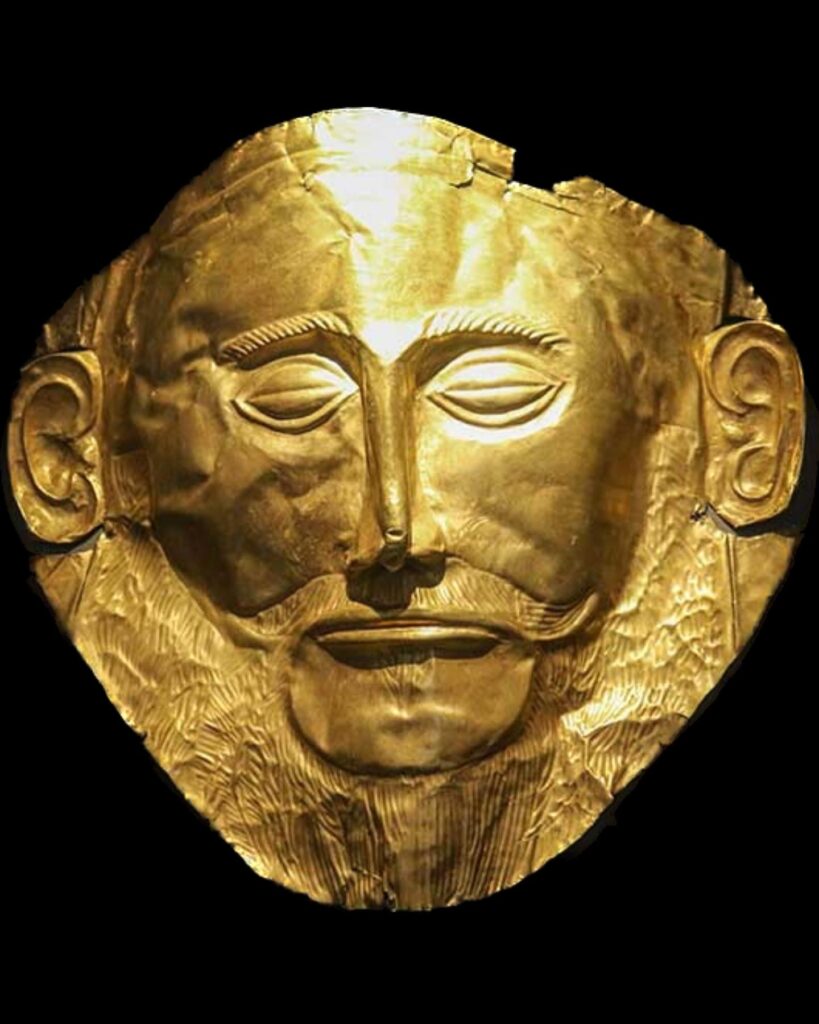

These are three of the seven masks found during Heinrich Schliemann’s famous late 19th century excavations of Mycenae.

They were found over the faces of men (and a boy child) in shaft graves within the grave circles in that wondrously fortified citadel, and clearly marked out the individuals buried with them as men of significant power and wealth. They are not death masks in the sense that they were moulded to the deceased’s face, but rather gold sheet hammered over a wooden core and with those marvellous details further incised onto them. And they are weird to the modern eye, and (so-far) unique in the known Mycenaean koine.

Schliemann (who I find endlessly fascinating) – a businessman turned Trojan War fanatic turned amateur “archaeologist” with the best luck of anyone in the game before or since – is an easy person to malign or otherwise poo-poo. He was frequently wrong in his dating and bombastic attributions, and made a righteous mess of some stratigraphy (especially before employing the services of the pioneering and scientifically inclined Wilhelm Dörpfeld.)

His shameless self-promotion attracted criticism during his life-time and after, and among other things he was accused of salting his digs with especially juicy finds, the so-called “Mask of Agamemnon” (the third photo in this sequence) being one of them. (The style of this last one was a bit different in style to the other’s wonders whether the handlebar moustache aroused suspicion, being rather close to Schliemann’s own facial hair…).

That mask (and the others) have universally been accepted as genuine, but likely far earlier (ca. 1500 B.C.) than the historical Agamemnon might have lived). And, in the end, it matters little that it was not the death mask of that mythical king.

Near the end of his life, Schliemann humorously apparently said: “So this is not Agamemnon? …these are not his ornaments? All right, let’s call him Schulze.”