For much of its ancient Greece was a ‘Thalassocracy’ – its settlements clustered close to the coast and inhabitants living and dying by the sea’s bounty and inherent dangers. It is difficult to fully comprehend how the Mediterranean determined daily habits and religion, drove innovation and warfare, and facilitated migration and trade.

The behaviors and superstitions of Archaic colonists has long been of interest to me, and the way they carried their local traditions, cults, and pottery with them. Boldly striking out on rickety ships, and gratefully erecting shrines and sanctuaries to commemorate safe passage (sometimes even using the lumber of their vessels as timbers in these early sacral constructions).

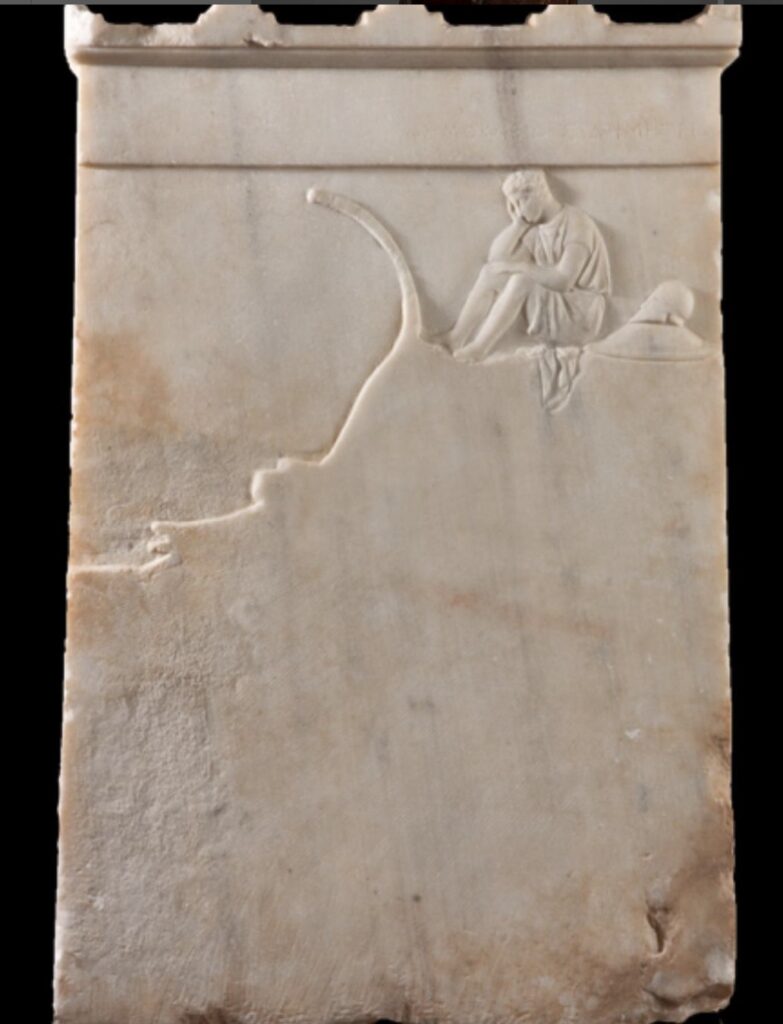

After a week punctuated by two astonishing and very different tragedies at sea (and I refrain from remarking upon the merits of the motivations driving them, or the relative human cost vs. media attention) this memorial stele now in Athens dating to ca. 400-390 B.C. seems especially poignant.

Artistically it is as powerful as it is stark, with a young man perched high above a craggy promontory marked by the prow and ram of a battleship, his helmet and shield behind him. He gazes contemplatively, head in hand, at the sea before him with the implication being a maritime death.